The first chapter of I Need my Yacht by Friday – True Stories from the Boat Repair yard.

“Reality is the leading cause of stress amongst those in touch with it.” – Jane Wagner

It’s December fifth, minus ten Celsius, and cold as hell building ships in North Vancouver. We shipwrights stand on pieces of plywood as we work so the steel deck doesn’t suck the heat from our bodies. But it’s worth it: the union job pays eighteen dollars an hour, the most money I have ever earned. Due to my wonderful new wage, and another child on the way, Louise and I sold our tiny two-bedroom house in Surrey two months ago and bought a four-bedroom house in North Vancouver close to my work.

Each time I fire the Hilti gun, there’s a satisfying ka-chunk and puff of acrid, grey smoke as the explosive charge fires a nail into the wood. Once I’ve cut the plywood bulkhead to shape, fastening it in place is easy. I space the nails eighteen inches apart. Ka-chunk, ka-chunk, each nail pins the wood to the steel tab to form part of the cabin wall. It’s three o’clock, one hour before quitting time. I’m thinking about the Christmas presents I will buy my wife and three-year-old son—maybe some perfume for Louise and a Green Machine riding toy for Steve.

Someone comes into the cabin behind me. Before I can turn around, Ernie the shipyard superintendent, in his white coveralls and handlebar moustache, barks out, “Baker, you are laid off as of four o’clock today.” His words leave me gasping for breath. My heart starts to pound, and I feel weak at the knees. Jesus—not now, not right before Christmas!

On that day, December 4, 1975, Ernie’s announcement changed my life forever.

<><><>

At 4.00 p.m. the loud klaxon reverberated throughout the shipyard, signalling the day’s end. The clang of building steel ships came to an abrupt halt as 220 men downed tools and headed toward the time clocks. Moving like a sleepwalker, ashamed and speaking to no one, I packed my heavy toolbox out of the shipyard.

My buddy Frank saw me carrying my tools. “Hey, taking your tools home to do some work on the weekend?”

“No. Laid off,” I replied, feeling worse for having said it out loud.

“Shit, you gotta be kidding me! Right before Christmas?” He grimaced and shot me a sideward glance.

“Yeah.”

“Wow man, that sucks. I’m sorry.” Sympathy helped.

I drove home in a daze. Houses, cars, and trees crept by in slow motion. I reached my front gate, put the handbrake on, and sat silently on the street wondering what to say to Louise.

The aroma of Louise’s shepherd’s pie greets me as I walk through the door.

“I’ve been laid off.”

“What?”

“I’m laid off from work as of today.”

“What are we going to do, Rod?” Her shoulders slumped and her blue eyes looked straight into mine. She was scared, which increased my panic—usually she was calm. After a couple of hours, the panic sank into worthlessness. What kind of breadwinner loses his job?

Buying the house two months previously had made me proud. Our new home came equipped with four bedrooms, a fireplace, a basement, a carport, and lovely front and back yards; plus, it was situated in a nice neighbourhood close to schools and shops. Getting fired flipped the joy of home ownership into an economic nightmare—one I had to fix. Louise had decided to be a stay-at-home mum and stopped working two months before Steve was born. So this was my problem to solve. No one was going to knock on my door and say, “Hey Rod, heard you’re out of work and have a family to support, I’ve got a job for you.”

I thought back to Dad. He had died when I was eighteen, but left a strong impression on me of the male as a resilient provider. When I was ten, he’d lost his job as a welder halfway through having our bungalow built. Mum was five months pregnant with my twin sisters. I remember Dad’s worried face. It was up to him, the head of the family, to find a solution. Sometimes we went with him for job interviews and watched him walk back to the car pursing his lips and shaking his head. Finally, after seven weeks, he found work. We were saved. Our lives could move forward. I had to do the same; it wasn’t a choice. I could hear Dad’s wry voice echoing from the past, saying, “Everything is easy, if you know how.” Male code, which meant his life learning, had been acquired through making mistakes. I had no idea how to become instantly re-employed. It would be a question of trying everything, and quickly, before we defaulted on the mortgage.

That evening Louise watched All in the Family on TV while I lay on the bed in the dark, not in the mood for Archie Bunker. Not in the mood for anything. When she came to bed, we didn’t speak. There was nothing to say.

I spent Saturday morning scanning the Yellow Pages and writing down the addresses of all the boatbuilders and shipyards within driving distance. After a weekend of worry, I launched myself towards possible employers. After three or four refusals, my confidence waned but I continued to try and sound upbeat.

“Hi, I’m a boatbuilder. Just wondered if you were hiring now or in the near future?”

“No, sorry, wrong time of year. Try again in the summer.”

The summer? Even a month without wages would land us in debt. By Friday, after seven refusals, I was at the end of my list and frustrated with offering myself over and over, only to be refused. Regret, self-pity, fear, and anger churned inside me like thunder in a valley unable to escape. Blaming someone, anyone, would have felt much better, but no one sprang to mind—except Ernie the foreman, or maybe myself: When I started working at Bel-Aire, I worked so fast that the shop steward, Bill, pulled me aside and said I was showing everybody up and to slow down. Two weeks before I got laid off I saw a new young helper busting his gut cleaning up the yard. Feeling helpful, I walked over to him.

“Hey, buddy, slow down. Nobody works hard here. You’ve gotta ease up. It’s not expected. People get pissed off if you work too fast—look around you.”

Bill, the shop steward, saw me talking to him and walked over to me as I headed toward the coffee truck. “What did you tell that guy?”

“Same as you told me. Just wised him up, told him to slow down, that it would upset people if he worked so fast.”

Bill raised his eyebrows. “Rod, that young fella is the boss’s nephew.”

Having no success finding work in boatyards, I decided to try looking for construction work and drove down to Capilano Mall, where they were building a new Sears. I found the foreman.

“Looks like a pretty big job here. Need any carpenters?”

“You union?”

“No.”

“No job here then, unless you know someone.”

Someone in the union or someone in management? I felt resentful. I knew no one in either, but was still a guy trying to feed his family. As a recent immigrant, I didn’t have any connections like old school friends or blood relatives that I could turn to.

Unions were the reason I had gone into boatbuilding. Upon immigrating to Canada a few years earlier, a friend had told me I should get into the trades. It had seemed like a good idea and I tried to get an apprenticeship as a plumber, an electrician and a carpenter, but they were all union. It was a catch-22: You couldn’t get a job unless you were union but you couldn’t join the union unless you had a job. Boatbuilding was non-union and I found work as an apprentice boatbuilder.

Two weeks without wages, one week until Christmas and the mortgage was due on the first of January. I bought a Vancouver Sun newspaper every day and scoured the Help Wanted columns like a man panning for gold. No nuggets of work showed up. The warmth of Christmas spirit was all around, but couldn’t penetrate my cold cloak of despair.

I helped Louise and my three-year-old son, Steve, decorate the Christmas tree. His face was aglow with delight as we attached the glittery ornaments.

“Christmas is coming soon, isn’t it, Daddy?

“Yes, son, pretty soon.”

“Are we going to have lots of presents?”

“Yup, lots of presents.”

Louise painted the living room mirror with a colourful Christmas scene as she did every year. The gifts were chosen frugally—some fruit for stocking stuffers, storybooks from us, and the grandparents supplied the larger gifts—nothing different that a child would notice. We went to my mother-in-law’s as usual for Christmas dinner. Everything was the same but different.

Our good friends Chris and Ginny asked us over for lunch on Boxing Day. They had just bought a house on a beautiful treed lot with a creek. I wasn’t feeling celebratory —self-doubt and “poor me” had taken over.

“Come on, Rod. You can’t mope around the house all day.” Louise was right. I was becoming morose.

Our hosts provided a lovely meal despite Ginny’s dissatisfaction with her out-dated kitchen. Ginny wondered if I would be interested in building them a new kitchen. Would a drowning man clutch at a straw? Yes, I was very interested! They said I could start in two weeks—a beacon of light flashing in the gloom. There would be money coming into our household for at least eight weeks.

My new job as kitchen builder started on January 15, 1976. I bought a used table saw from the Buy and Sell paper and borrowed my father-in-law’s utility trailer to haul away the old kitchen and fetch materials for the new one. Instead of the eighteen dollars an hour earned at Bel-Aire, I offered my services at seven dollars an hour; I couldn’t risk refusal. I had never built a kitchen before, but would soon learn—fear adds wings to learning.

Ginny wanted a wrap-around kitchen with cabinets made of plywood covered with white plastic laminate. I had to get the measurements exact. You can’t shave plastic laminate to fit, like you can wood. It was scary. There was no foreman to direct me, and no fellow workers to discuss the job. Plus, the work was being done for friends. If I took too long, or somehow displeased them, it could sour the relationship.

At 9.00 p.m. on the fourth of March, Louise started having labour pains. We woke up Steve. “Mum’s having the baby now. We are going to drop you off at Grandma’s house.”

“Oh, good. Can I have pancakes?” Grandma always made pancakes.

On the fifth of March, 1976, at 4.00 a.m., our healthy baby boy, Michael Rodney Wilson Baker, was born. I asked to attend the birth. “If you must,” said the matron. I hadn’t been allowed to attend Steve’s birth, but hospital restrictions had mellowed in four years.

After four hours of labour, Louise’s face broke into a huge smile as our second child finally forged his way into our world. The nurse cleaned him up and handed me my newborn son. His blue eyes stared up at me as I rocked him slowly in my arms and inhaled the smell of new baby. I looked at him proudly but felt uneasy. He didn’t know the man holding him was unemployed and bringing him home to a house he couldn’t pay for.

Building Chris and Ginny’s kitchen lasted longer than I thought, but came to an end a week after Mike’s birth. My stomach started to churn. I was keeping my head above water, but only just. Ever helpful, Chris told me that a colleague of his, Bernie, wanted a kitchen built—another life ring floating towards me. I grabbed it with both hands.

Bernie and Sue lived in a beautiful house, located in a grove of arbutus trees, with a peek-a-boo view of the sea. Sue dreamed of a kitchen with knotty pine cabinets. I was the man to make it happen. Their old kitchen got ripped out, the trailer loaded with tongue-and-groove pine, and their new kitchen started to take shape. The smell of fresh-cut pine filled the kitchen space as I fabricated the cupboards. During breaks and lunch, Sue offered me coffee and cake, and we watched the highlights of the 1976 Olympics in Montreal. Nadia Comaneci got a ten—the first ever perfect score in gymnastics.

As Sue’s kitchen cabinets were getting the final touches of stain, the familiar gnawing crept back into my stomach. Thank God for word of mouth: Bernie was in the insurance business and a client of his who lived aboard a houseboat in Coal Harbour needed some work done. His name was Tony, a local artist.

Tony said that his Japanese girlfriend was moving in, and he wanted to spruce up his living quarters. I upped my rate to eight dollars an hour.

“How come you charge so much?” asked Tony.

“Well, see this captain’s bed I am building for you? In ten years’ time, each of the four drawers should still be working, unlike your paintings, which once painted, have no working parts, just hang on the wall and last for life.”

No comment from Tony, but he frowned and gave me a strange look.

About three-quarters of the way through Tony’s job, an idea I had never remotely considered was launched across my bow. I couldn’t tell if it was a lifeline or a hangman’s noose.

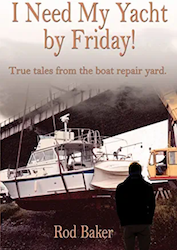

I Need My Yacht By Friday: True Tales from the Boat Repair Yard

(Published 2018)